So, this past week, my girlfriend and I traveled to Jamaica to celebrate her birthday. We stayed in Treasure Beach, St. Elizabeth, which I thought would provide us a more authentic Jamaican experience vs. a major city like Montego Bay.

It didn’t disappoint: Treasure Beach was lovely, the people were all kind and helpful, and my girlfriend and I had a blast. But one thing that really fascinated and frustrated me was the quality of the roads in Jamaica. One could see how much Hurricane Beryl had damaged them. However, disasters often highlight already existing inequities. In the case of Beryl, it laid bare the ways in which colonialism and its lingering race and class divisions have bifurcated Jamaica. Because I am the way I am, I decided to dig deeper and investigate why the roads are like this.

To begin, a brief word on the political importance of roads. Beyond their literal importance (we need them to get around), roads are uniquely political. “Roads […] become dynamic sites for reflecting on the political, economic, and social issues facing the region…”(Fadellin 2020). Public roads built and maintained by the state show who and what the state deems to be important. The ways in which the state builds,maintains, and polices roads show its priorities.

What gets built and who it is built for means something.

Roads “press into the flesh” certain attitudes, assumptions, and modes of being (Fadellin, citing Appel et al. 26). In certain, non-sensational ways, roads and other infrastructure can be used to enact “violence” upon certain populations. Id. For example, look how the interstate highway system in the U.S. was used to destroy Black communities.

A Short Political History of Jamaica (and its roads)

Colonial Period

The history of Jamaica’s roads is largely tied to its history as a British colony and major site of chattel slavery. When England took Jamaica from the Spanish in 1655, it was largely due to the fact that Spain had not been able to turn the island into a profitable enterprise and had failed to significantly invest in it. This disinterest in building infrastructure in the island was reflected in the island’s geography, where pretty much all development was concentrated in the north of the island or around ports and plantations.

This didn’t really change when the British took over — while plantation infrastructure was relatively well-developed, the roads connecting other parts of the island was virtually non-existent. This has not really changed in the time since the abolition of slavery. As Soile Ylivuori notes in “Settler Colonialism and Infrastructural Decay,” “the general condition of Jamaica’s road infrastructure seems to have changed surprisingly little in the past three hundred years.” (2024). She goes on to note that the geography of Jamaica’s infrastructure (and by extension its roads) is deeply tied up in race and class:

“On a social level, [infrastructure] contributed to the production of racialized, classed, and gendered difference in the West Indies. Muddy roads were easier to travel for a White man on horseback than a White woman in a carriage (which often got stuck in the mud or capsized) or a Black enslaved person traveling on foot. On plantations, enslaved workers were generally housed in “miserable huts” with “bare earth” floors, often placed in damp and unhealthy parts of the plantation, as the “planters have wisely fixed their own habitations in general upon elevated spots, in order to be secure from floods, which have sometimes been so violent on the lower grounds, as to sweep away buildings, cattle, and Negroes.”

She relates this to the idea of decay. The island’s climate rapidly destroyed things like roads, bridges, and houses, and race, gender, and class dictated whose infrastructure was maintained. The housing for enslaved folks was poorly maintained by the white settlers, while their own plantation homes were built up high with strong materials. This was doubly cruel because it was the enslaved folks forced to do the repair labor.

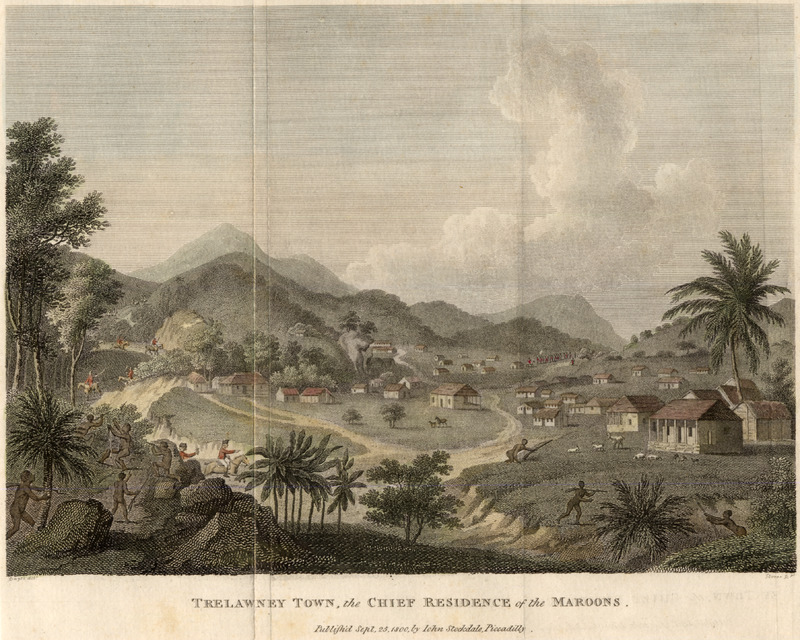

On the flip side, the challenging tropical climate was a useful tool in Maroon (those who escaped captivity and fought for freedom) resistance. As Ylivuori notes, “free Maroon towns, such as Nanny Town in the Blue Mountains, were deliberately built in remote and challenging locations for strategic reasons. Difficult to access and therefore to maintain, […] Maroon dwellings were also more vulnerable to tropical decay than those of White settlers.”

While the decay inherent to the island climate often meant that Black Jamaicans had to deal with poor roads and other bad infrastructures, it also assisted them in the fight for freedom. “[S]ince slavery was organized as an infrastructure network, it was highly dependent on material things such as ships, roads, and plantations—the decay of [those things] could also work to destabilize existing power structures.” Id. at 15. In this way, the poor general quality of Jamaica’s roads had the dual effect of entrenching and destabilizing power relations.

This became especially clear during the Maroon Wars, where the Maroons effectively exploited the lack of roads as part of the guerrilla tactics they employed against the British. Id. However, once slavery was abolished in Jamaica and Black folks won the right to vote, these structural disadvantages again served as a hindrance to Black political and economic progress.

The 1938 General Strike, The Rise of the Two-Party System, and Independence

At the turn of the 20th century, a Caribbean-wide workers movement washed ashore in Jamaica, bringingnew light to plight of Jamaica’s working class and, by extension, the deficient infrastructure that they had to deal with. The Great Depression basically killed the Jamaican sugar industry, leaving millions without work or with unlivable wages. In response, workers turned to organizing to try to improve their lots. This was met with brutal repression. The workers uprisings that began in 1929 came to a head in 1938 with a general strike that shocked the British Crown and presaged the end of colonial rule on the island.

Workers organized into a few different organizations. The two most prominent (at least at first) were the Trade Unions Council (TUC) and the People’s National Party (PNP), a left-wing/democratic socialist party. The PNP’s platform was fairly radical at the time, seeking independence from the British, universal suffrage for Black and brown Jamaicans, a strong social safety net, and spending on infrastructure.

One of its founders, Norman Manley, was inspired by British left-wing policies to pursue an aggressive reform program. The PNP’s project was initially fractured when one of its leaders — Alexander Bustamante — formed a rival organization — the Bustamante Industrial Trade Union, split the PNP/TUC base. Bustamante, arrested by the British and released after an intense wave of public outcry, became a folk hero and, riding this wave of popular sentiment, became the “uncrowned king” of Jamaica. Bustamante’s influence was augmented by the sudden interest that the United States, mobilized by World War II, took in the island. In 1944, the British relented and passed major electoral reforms, including establishing a parliamentary government and establishing universal suffrage. While well-short of the demands that initially animated the uprising, it was a major win.

In 1943, Bustamante formed the Jamaican Labour Party (JLP), a political outfit that was largely meant to expand his already considerable influence on the eve of independence. In the 1944 elections, the first with universal suffrage, the JLP beat back the PNP thanks largely to the support of working class Jamaicans.

Despite this working class mandate, Bustamante’s JLP government quickly became an organ of the British Empire and a defender of American economic interests. He defended British economic interests with verve, most notably moving to prevent the nationalization of Tate and Lyle, a British sugar company that had a near-monopoly on Jamaica’s agriculture. Tate and Lyle’s monopoly only exacerbated the centuries-long divestment in Jamaican road infrastructure, as public monies went towards bolstering the power and profits of a single conglomerate.

In addition, the JLP aggressively courted foreign companies using the promise of low taxes and no regulation — a precursor to the modern neoliberal cocktail — as a means of bootstrapping Jamaica’s economy. This worked on paper — GDP and other indices went up — but working class and poor Jamaicans didn’t see any material benefits.

This scuttling of working class and anti-colonial elements would continue into the 1960s, where a vote on Jamaica’s entry into the West Indies Federation — an effort by Manley and other progressives to build international anti-colonial solidarity — narrowly failed thanks in large part to Bustamante’s influence. This led to a stripped down freedom demand that culminated in Jamaica becoming a commonwealth nation. Nominally independent but still under the British Crown, the extractive relationship between Britain and Jamaica was maintained, now with rich Jamaicans as the island’s managers.

The Manley Moment

The pursuit of foreign investment and attendant lack of investment in the nation’s infrastructure and people caught up to Jamaica in the 1960s and early 1970s, when the collapse of the bauxite industry again created the conditions for an uprising. This coincided with the Black American Civil Rights and Black Power movements, which inspired similar freedom struggles across the Black Diaspora.

The co-mingling of class struggle and Black radical politics was very potent, and the JLP government used brutal violence to try to suppress it. In 1968, when the JLP government refused to allow prominent Black academic and activist Walter Rodney. The riots that this spurred ballooned into a broader reckoning that saw Jamaicans again embracing anti-colonial and worker-centric politics. This is the moment in Jamaica’s history from which its most well-known cultural products, most notably reggae, emerge.

The political result of this moment was the elevation of a new PNP, one that partly rejected the moderation of the 1950s and 1960s and instead pursued a social democratic program. Led by Michael Manley, son of PNP founder Norman, the PNP remade itself into a left populist party that spoke the language of the people (at times literally, as Manley would often use Jamaican patois to campaign) at a moment when Jamaican nationalism had come into fullness.

The Michael Manley-led PNP undertook a series of increasingly radical reforms that sought to take full advantage of the popular mandate produced by the Black Power movement. An adult literacy program emulated the mass education programs in other left-wing nations, a public housing initiative sought to curtail homelessness. However, the two most radical programs are also the ones with direct implications on the state of Jamaica’s roads to this day: Project Land Lease, where the government acquired and then leased out land in hopes of putting it to productive use, and the nationalization of foreign-owned transport companies.

The purpose of both of these programs is clear — the PNP sought an industrial and economic policy of building up the poor and working class through direct redistribution of resources and the construction of both the physical and economic infrastructure needed for upward mobility. The land redistribution policy highlights exactly what the problem was for Jamaica’s road infrastructure — a small group of wealthy companies and landowners owned most of the land, and this led to asymmetric development and, in some cases, full-scale divestment. By ceding the lands to the poor and working class, the PNP government sought to shift this dynamic. The nationalization effort sought in part to unshackle the state of Jamaica’s infrastructure from bourgeois interests. In particular, the nationalization of trains and buses were meant to provide reliable transport across the country, connecting rural and poor areas to cities and wealthier ones.

This effort at fighting the vestiges of colonial rule and empowering the working class (and fixing the damn roads!) was ultimately cut short by an economic crisis and American meddling. As a result of socialist Jamaica’s staunch defense of other anti-colonial efforts in Africa and Asia, as well as its growing closeness to Cuba, the United States reduced trade with it and sought to box it out internationally. It also withdrew aid and discouraged tourism, which had become (and still is) a huge industry in Jamaica. Henry Kissinger, architect of some of America’s greatest foreign policy crimes, personally visited Jamaica to try and coerce Manley into abandoning Cuba. It did not work, and from then on, the U.S. actively sought to destabilize Jamaica’s government.

The U.S., through the JLP and its new head Edward Seaga, sought to use gang violence as a means of diminishing the PNP’s power. This strategy of using economic isolation and gang violence to challenge leftist governments in Latin America should be familiar to anyone with knowledge of the CIA’s activities in Argentina, Guatemala, or the Dominican Republic at that time. The resultant gang violence ravaged the country and further weakened Manley and the PNP’s political project.

In addition to the literal violence of the JLP’s gangs, Jamaica’s nascent socialism was stymied by insufficient funds. With foreign companies withholding investment and the IMF subjecting Jamaica to draconian loan terms, the country’s economic prospects darkened even as some of the government’s social spending produced meaningful increases in quality of life for the nation’s poor and working class. In 1977, after almost a decade of struggling against international capital, the PNP government accepted the IMF terms and began scaling back some of the major social democratic reforms that had ingratiated them to the working class. The living standards of the working class fell, and so too did efforts to fix the vestigial physical manifestations of colonial rule.

Modern Day — Neocolonial Retrenchment

Since then, Jamaica’s road infrastructure has largely been financed through public-private partnerships and loans from international organizations like the IMF. These efforts have concentrated development exactly where you’d expect — the U.S. and private lenders want to see return on their investments, and the IMF only wants to invest in economically “useful” developments (e.g., roads that bolster global capital).

Perhaps the most significant development has been the entry of China, who invested billions in Jamaica’s infrastructure through its Belt and Road Initiative. The BRI is China’s soft power colonial project, seeking to use debt and economic entanglement to force nations into its orbit. The United States and the West have largely let this initiative play out unimpeded, and the result has been a proliferation of fancy Chinese-backed infrastructure projects across the global South.

However, this kind of neocolonial parachuting is ill-fit to the actual needs of Jamaicans: the North-South highway largely connects two tourist destinations and isn’t regularly used by native Jamaicans. The tolls make the road prohibitively expensive for most Jamaicans, and the money doesn’t even go to the government, but to a private Chinese company. The near-billion dollar debt produced has made the economic plight of poor and working class Jamaicans even worse. In essence, it’s yet another example of how colonial (or neocolonial) attitudes have shaped Jamaica’s roads — the road serves the interests of the powerful, of foreigners, and of the wealthy, but not native Jamaicans or the working class.

The result of all this is the patchwork we see today. Some major thoroughfares are well-maintained, and the roads in major cities like Montego Bay are pretty good. But outside of that, the situation deteriorates pretty quickly. The Prime Minister of Jamaica, Andrew Holness (JLP) declared the poor roads a “national emergency” and pledged immediate funding and fixes, but it remains to be seen if these funds will go towards areas or projects that aren’t immediately beneficial to capital.

Why does any of this matter?

By this point, you’re probably thinking, “David, why couldn’t you just enjoy your vacation and not think broadly about the historical context and political implications of it?” Well, for me this is important for three primary reasons. First, I don’t like being frustrated or upset by something without knowing why that thing is how it is. To simply be mad that the roads connecting Jamaica are poor is, to me, a half-thought. The full thought is to ask why and to understand that why in context. This is the why and the context.

Second, I think there’s an impulse among Americans when traveling to see foreign countries as inscrutable. We go to these far-flung, “exotic” destinations and never stop to think about how those places are constructed or what led them to be how they are.

That bugs me. The intellectual benefit of travel isn’t just to lounge on a beach somewhere, but to expand one’s world, to test one’s assumptions against new knowledge and experience, and to use the product in service of something.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, is the continual recognition that the systems that I and other leftists rail against have material, real-world consequences. Capitalism’s evils are often abstracted out in leftist discourse, we talk about systems and dialectics and never quite make the connection between those things and the world that most folks actually live in. To paraphrase the late Mark Fisher, there’s a tendency among armchair leftists to live solely in the world of theory, with no intention of connecting that theory to the real world or any real political action.

But here, we have a very concrete (no pun intended) example of how colonialism, neocolonialism, and capitalism have affected the lives of millions of people. In Jamaica, the quality (or even existence) of roads is largely contingent on your subject position. The very structure of the Jamaican road network is a vestige of the plantation economy and colonialism, the locations of major cities a result of both natural and political forces. To see this is to better understand what shapes and animates our world, and that’s fascinating and frustrating in equal measure.

Additionally, it demonstrates yet again how the moment we’re living in is colored and presaged by what happened before. The modern crisis in Jamaica’s roads is not simply a product of this year’s storms, but of long-term divestment and colonial logics. The story of Jamaica’s dismal roads is also the story of British colonial violence, American imperial incursion, and of the Jamaican people’s resilience and fight. At every step of the way, the Jamaican people — whether it was the Maroons, the trade unionists, or the Black Power protestors — stood up against oppression and extraction and fought for the country (and the roads) they deserved. Every major shift in Jamaican politics has been driven in no small part by the valiant efforts of these freedom fighters. This serves as a potent reminder that politics is a bottom-up endeavor, one that only finds teeth when coalitions of the working class, the poor, and the petit bourgeois can come together and reject the status quo. That lesson is particularly salient in light of Tuesday’s post, where we discuss the ways in which the American Democratic Party’s defeat partially reflects its abandonment of the working class people that animated the New Deal coalition.

This is the first of what will probably be several posts about my trip, so I hope you all look forward to the next post, which will (maybe!) be less heady.